Monitoring: A Qualitative Analysis of Television for Children

Maria d’Alessio. Rai Eri, Rome 2009

By Norberto González Gaitano

“”He liked Dragon Ball so much that I had to buy him the entire series or else he would throw a tantrum. Then to make him behave, I told him that if he obeys me, I would buy him the action figures. I have no choice. The other day I brought him to the hair dresser and as soon as she saw him, she said ‘Would you like me to do your hair like Goku?’, ‘Yea, yea’, he responded…”.

There you have it: the story of the mother of John (4 years old) told in one of the interviews for the research on qualitative monitoring of the relationship between children and the media. The study was conducted and coordinated by Maria D’Alessio, Professor of Psychology at Sapienza University (Rome, Italy). It focuses on the programming of RaiSat Ragazzi (Rai Satellite for Children, Italy).

The example illustrates one of the many results of these studies, one concerning identification: “the television narrative has quite different characteristics than those of fairy tales. Myths embody and demonstrate above all values and internal conflicts; and through symbols, they offer patterns of behavior. TV characters present lifestyles and are examples to be emulated, where behavior is more important than the interior disposition” (p.106).

The book gives an account of all the research commissioned by RaiSat Ragazzi and conducted over the time span of 1998 to 2008 in order to perform a qualitative monitoring of its programs using the benefits from a psychological research of child development previously carried out elsewhere. Questionnaires were given to children of different ages, to teachers, and to parents; and experiments were conducted in which children watched clips from a few selected programs. There were several indicators measured that allowed for the understanding of how children absorb the programs they watched and the effects influencing their knowledge and behavior.

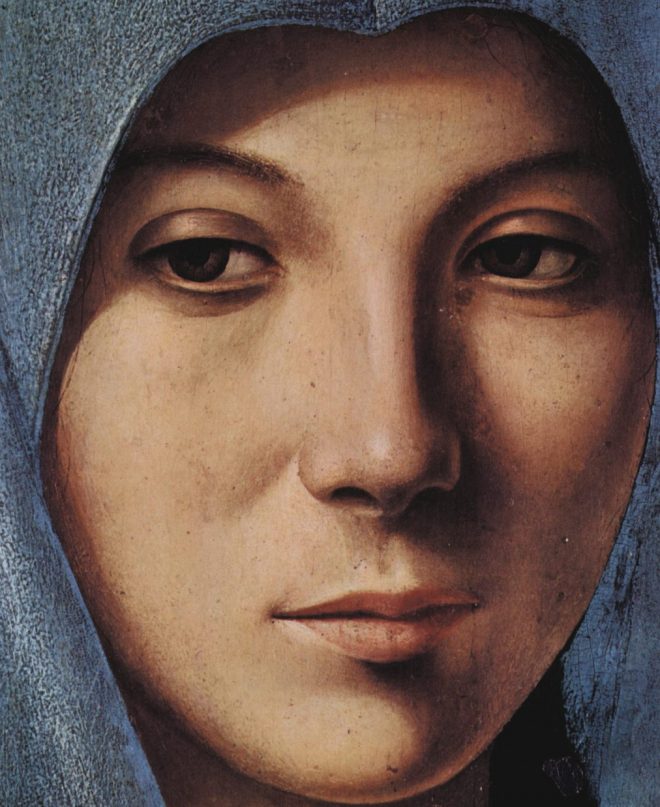

The book presents a brief description of the programs analyzed and includes drawings and photographs with an exhaustive appendix of all the research questionnaires used to measure the various “constructs” or indicators.

These are also presented in the explanation of the study in order to render the underlying concepts and outcomes more accessible to the reader. Below,

I present a summary of the most relevant results, based on each of the “constructs” or psychological concepts measured in the study.

Esteem, understanding, memory, identification process and attentional behavior

1. Esteem, which differs from the concepts of pleasure, preference, attraction, or even fun, although related to them, depends on cognitive development, on affective and motivational dynamics, and on the availability of the product. For example, although children understand more about cartoons because they are more simple and linear, they more greatly value programs with human actors. In the experiment reported, Grandpa Bruno (a human character) achieves a higher score than Teddy Bear (a cartoon character).

2. Program comprehension by children, regardless of format, is always greater than what parents imagine. Furthermore, research proves that “if children are watching television in the company of their parents, the effects will be different than a solitary enjoyment, whether it be on the perceptual, cognitive, or emotional level. ” Comprehension increases when parents often make comments during and after watching a program.

Furthermore, “the most productive situation is achieved when their parents discuss and talk about the programs with their children and help them to

take television content and make analogies and contrasts with their own lives” (p.73).

3. Memory obviously depends on age. Children of 6 to 10 years old are able to remember all the programs that are offered. For the youngest, the uniqueness and the strangeness of the situations experienced by the characters determine a more intensive memory. Then, that which the children remember does not coincide with what they prefer or with what they identify. The conclusion that flows from empirical observations on the memory is clear: “It is strongly recommended not to expose children to content that is unsuitable for them, regardless of age. In the case of very young children, lack of understanding means that undesirable content reaches the child without any cognitive filtering, leaving an indelible mark, even though it is unconscious. As for the older children, the more structured value system acts as a filter in the organization of one’s preference, but not on more automatic cognitive processes such as memory “(p. 104).

4. If it is true that television viewing creates what psychologists call “parasocial relationships”, which are “apparent relationships and emotional ties with a television character”, it is equally true that children have a greater critical capacity than you might have thought. From the age of 3, children are able to establish a boundary between reality and fantasy; from the age of 6 and up, they know that cartoon characters are not living beings, although they are emotionally affected by what they see. Between 9 and 10 years old, children infer a separation between the values that children represent in the programs from the children themselves, i.e. they realize that the child actors act. In any case, “the child, unlike the adult, does not empathize with the characters, but he absorbs emotions and values” (p. 110).

5. Regarding the option of entertainment television or educational television, the Italian research conducted by D’Alessio confirms the findings of other international studies. “The cognitive complexity of the

child leads him to remember, comprehend and appreciate more complex television content over simplified or trivial content” (p. 151). Films more greatly capture their attention than animated cartoons, although they say that they like cartoons. Still, the cultural stereotype that associates cartoons to children continues and becomes enhanced by the production of programs: 70% of the childhood schedule is filled with cartoons.

Comments

The volume, as the authors indicate in the presentation, thematically brings together several studies carried out over a period of 10 years. The tables and lists, provided during the work and in the appendix, are complete and exhaustive but do not specify in each research the characteristics of subjects studied, apart from their age. Furthermore, combining the results of studies by subject weakens the methodological indications of each study, except in the chapter on attentional behavior, which is more detailed. This is surely the reason why inconsistencies in the results were occasionally observed, such as those concerning understanding. Reading this book gives the impression that these studies were a replication of research conducted elsewhere in order to confirm the results obtained in other countries, thereby lacking its own suitable design while still targeting the Italian public.